I was born with my mother buried inside of me — disappeared by many violences, but especially the violence of my birth.

A daughter is sometimes called a thief. In the Korean dictionary, there are multiple idioms that say this. She is a beautiful thief. She steals from her mother. Her mother encourages this. She knows what violences her daughter has ahead of her.

Poet Kim Hyesoon writes, a Korean woman is full of holes. Each hole buries a woman disappeared by violence. As a Korean American woman, I too carry these women in holes of my own.

My grandmother disappeared in the midst of the pandemic. To process my grief, I searched for her in my photographs. I was shocked by how few I had. This absence helped me start to notice the figures in the margins.

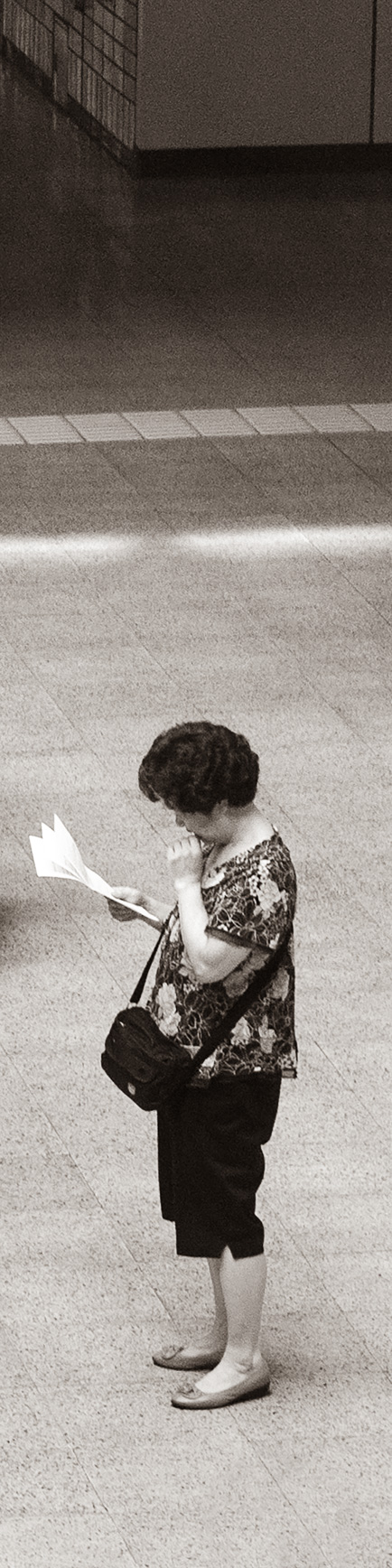

These are women whose movements are controlled by the hungers around her — often working, cleaning, or carrying food. They are laughing, dancing, poised, or bored. I became obsessed with finding them all, unsettled by the fact that despite what I was finding now, my lens had been focused elsewhere. I had embarrassingly waited for so many of them to leave the frame.

Over the past few years, I have become acutely aware of what it means to be visible and invisible at the same time. It can be just as painful to be seen as to be unseen — to be seen repeatedly can be its own form of erasure. How can we be visible without being seen as marginalized or other?

These images are cut from a collection of my own photographs, as well as photographs taken before the Korean War from our family archive.